Chapter 3, “Clean Up Your Spills!”, helps students

approach and develop strategies for dealing with complex

problems. These problems often do not have clear answers because

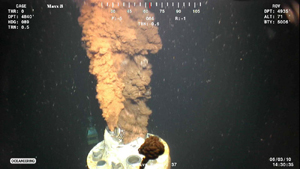

they involve competing constraints. For example, oil spills are

complex problems to solve. Solutions involve several

technologies. The questions of which technology to use and when

to use it do not have clear-cut answers. The solution depends on

several competing constraints such as type of oil, size of

spill, proximity to the coast, and cost. Students will analyze

these constraints and learn how to explain the choices they

make.

In the Engage activity, When Solutions

Seem Impossible, students will read a dialogue between two

engineers and think about competing constraints. They share

their prior thinking about constraints and how those constraints

might drive solutions in opposite directions.

In the Explore activity, Recovery Time,

teams of students make a model oil spill and determine how fast

they can remove it compared with the efficiency of removal. They

make only preliminary interpretations of the data they collect.

During the Explain activity, Possible

versus Impossible, students read the field notes of the

engineer from the Engage activity. These notes show a worked-out

example of how to make sense of a recovery rate versus recovery

efficiency graph whose data come from the Explore activity.

Students use this model to construct an explanation for their

data from the Explore activity.

In the Elaborate activity, Simulate

and Save, students read about other oil spill cleanup

technologies. Then they use a computer simulation to understand

how each technology affects the oil spill. Students apply what

they learned from the Explain activity to form an explanation of

how each technology works.

Finally, in the Evaluate activity, Choosing

a Solution, teams select a set of constraints, which drives a

solution to the oil spill cleanup in a particular direction.

Students explain their solution to a group of stakeholders.

Before beginning this chapter, students should have completed

the first two chapters of this module. It would be helpful if

they had some knowledge about data tables, making bar charts,

calculating simple percents, and graphing x-y data.

However, you can provide that information during the activities

if necessary. Students should also have basic computer skills,

as they will be using an interactive computer simulation during

the Elaborate and Evaluate activities.

Students may harbor misconceptions about the material they

will be studying in this chapter. We list some of these

misconceptions in this section. Do not take time to go through

them as a list of lecture topics for your students, but rather

use them to inform your teaching as the misconceptions emerge.

Many activities included in this chapter work to expose

misconceptions and help students develop better mental models.

The best answer means the same thing to everybody.

Solutions to complex problems often involve compromise among

several solutions or a blend of solutions. The solution that

one group advocates may not be the solution that a different

group supports. It is natural for middle school students to

believe that everyone thinks as they do. With time and

exposure to multiple solutions, students learn to incorporate

alternative views into solutions to complex problems.

All relationships between variables are linear and

positive. Linear, positive relationships graph as a straight

line with a constant, positive slope. These graphs are common

in school settings, but certainly are not the only ones found

in nature, business, and engineering. Many relationships graph

to curved lines and many form inverse relationships. With

exposure and practice, students will not jump to the

conclusion that as one variable increases the other also

increases by a constant proportional amount.

Problem solutions always have one correct answer.

School experience often teaches students that there is one

correct answer that receives full credit. In real-world

settings, this is often not the case. Problem solutions often

vary depending on physical constraints and the subjective

beliefs or political sway of stakeholders.

Disperse is the same as remove. Dispersing oil

(spreading it out) does not remove or convert the oil into

something else. In dispersing oil, the amount of oil remains

the same. Dispersing redirects the oil from storage barrels

and landfills to the water column or ocean floor. Over time,

oil that is dispersed can be converted to organic by-products

by oil-eating organisms.

One must get it right the first time. School

experiences can reinforce the idea that only right answers

count and that making mistakes along the way isn’t common.

In fact, engineers reach solutions in a series of steps. Those

steps often involve mistakes. Engineers learn from those

mistakes and move forward toward a final solution. Engineers

view themselves as works in progress.

The Explore activity is more material-intensive than the

other activities in this chapter. You may need some time to

collect the materials needed for this activity. It is best to

conduct this activity in a room with sinks and access to water.

For the Elaborate and Evaluate activities, you will likely

need access to computers for two class periods. Be sure to

reserve computers or a computer lab in advance of these

activities.

The Materials and Advance Preparation sections for each of

these activities provide more information about the necessary

preparation.