In the Explore activity, you investigated a set of miniature events. You might be wondering how the miniature events are like actual events, such as a wildfire (See figure 2-12.), drought, flood, tornado, or hurricane. In this Explain activity, Presenting Events, you and your teammates will become experts on one type of event. Then, you will teach other students in your class how the miniature event is like the real-life event. Materials

Set up a new page in your technology notebook for a new activity. Remember to include the title and the date. Enter this activity in the table of contents.

In this activity which covers Steps, 2, 3, and 4, you and your teammates will read about one type of natural event. When you know which natural event you will be learning more about, think back to the miniature events in the Explore activity. With your teammates, think of

- two ways that the similar miniature event is like your team’s natural event

- two ways that the similar miniature event is not like your natural event.

Write your answers in your technology notebook. Hint

Before you begin the reading, look through the following questions with your teammates. As you read, look for the answers to these questions.

- What causes this type of event?

- What can affect how serious this type of event becomes?

- How does it affect humans?

- How does it affect the environment?

- What responses to this type of event might humans have for safety and for changing the event’s negative impact on the environment and the community?

- What are some examples?

- How is the actual event like the miniature event you observed? Hint

Read about your natural event and discuss the questions with your teammates. If you do not agree on the answers to the questions, refer to the information from your chart or refer back to the reading. Hint

In this part of the activity, you will learn about other types of natural events from other students in your class who were not in your first group. You will meet in a new team of five students. This new team will include one student who is an expert in each one of the natural events. You will need a copy of Master 2-2, Natural Events. Hint

In your new team, you will take turns explaining the natural event that you learned about to the other team members. As you listen to the other students, fill in the natural events chart that you drew in your notebook. Be sure to ask questions if you need more information about any of the natural events.

Be prepared to join in a class discussion of the natural events. You should be ready to answer questions about any of the natural events, not only the event you read about first.

Background Information

Reading 1: Fires

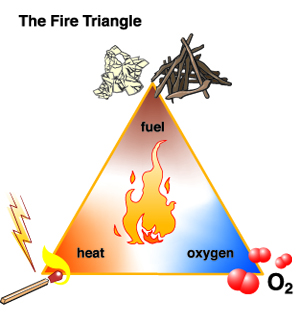

A wildfire is an uncontrolled fire that often starts in the wilderness. Wildfires can also be called forest fires if they start in a forest. For a fire to start and continue burning, it requires fuel, oxygen, and heat. Fuel is anything that burns. In a forest fire, the fuel could be trees, bushes, grass, or debris on the ground. In a house fire, furniture, the wood frame, carpeting, clothing, and other household items serve as fuel for fires. (See figure 2-14.)

Oxygen is needed for something to burn. Because it makes up about 21 percent of the air, oxygen is usually available. The process of something igniting, or bursting into flames, is called combustion. During combustion, oxygen combines with fuel to make a fire. As the fire burns, it creates heat. This heat causes higher temperatures that help more things burn. The hotter the fire, the easier it is for oxygen and fuel to combust.

Together, fuel, oxygen, and heat represent the fire triangle. (See figure 2-15.) Just as a three-legged stool will not stand up if one of its legs is missing, a fire will not keep burning if fuel, oxygen, or heat is missing. To put out a fire, firefighters seek to eliminate one or more of these elements. For example, when fighting a forest fire, they will try to remove fuel from the path of the fire by creating fire lines, long ditches in which all of the vegetation has been removed, either by hand or by bulldozer. (See figure 2-16.) When the fire reaches the fire line, there is no fuel left to burn. Also, firefighters may spray water on a fire to reduce its temperature, or they might cover it with dirt to cut off its oxygen supply. A fire will go out unless it has fuel, oxygen, and heat.

A fire burning in a building or forest creates convection currents (air movements). The rapidly rising air and hot smoke over the fire pull in the surrounding air. This makes a fire stronger and harder to put out.

Weather conditions play an important role in whether a fire keeps burning. Dry, windy conditions increase the chances that a fire will start. Rain and snow, however, help keep fuel cool, so it does not ignite. Rain or snow also can smother the flames by keeping oxygen out. These wet conditions, however, will only stop low-temperature fires.

The temperature and moisture of the air can influence how easily a fire will start or how well it continues to burn. It is very difficult to start a fire at very low temperatures (below –18°C, or 0°F). The possibility of fire also decreases if the humidity (the moisture in the air) is high. Moisture in the air tends to keep fuel moist. This, in turn, keeps the temperature of the fuel low and reduces the chance of combustion.

Some fires can be helpful. For example, after fires burn in some forests, it becomes easier for new trees to grow. After a fire, seedlings receive more sunlight because there are few older trees and tall trees to block the light. Some species of trees, such as lodgepole pines and jack pines, need the high temperatures that fire provides. (See figure 2-18.) The heat opens their cones and allows the seeds to be dispersed.

In wilderness areas, we can see patterns of fire because trees and grasses act as fuel. Lightning strikes can easily ignite woodlands and grasslands when it is dry enough and there is enough fuel. When scientists studied the giant sequoias in California, for example, they found that fires occurred in the sequoia forests about every eight years. These fires did not damage the trees because of their thick bark. Instead, the fires cleared the ground so that new trees could sprout. The pattern ended when humans began putting out fires in parks where the sequoias grow.

Fires can benefit wildlife and animals that eat grass. When fires burn down trees or shrubs, grasses are often the first plants to grow back. People have begun to use this phenomenon in the plains region of western and central North America. By starting small, controlled fires, they have found that grasses will grow back in areas once taken over by shrubs.

In 1988, wildfires affected almost 1.2 million acres (about 485,600 hectares) of land in and around Yellowstone National Park. The summer of 1988 was hot and dry across much of the United States. The combination of heat, dry weather, strong winds, and lightning resulted in wildfires that burned more than one-third of the land in Yellowstone National Park. Nine fires within Yellowstone were caused by humans; 42 were caused by lightning. The fires burned from June until snow fell in September.

The 1988 Yellowstone fires started a controversy about managing fires. From the 1930s until 1970, park officials put out every fire. Then in 1970, the National Park Service started a new policy. Under this policy, park officials would let certain fires (mainly those started by lightning in isolated areas) burn. This allowed forests to go through their natural cycles. The fires would burn out the debris (mostly dead, decaying plant matter) that had accumulated on the ground. The burning of the debris would encourage new growth. (See figure 2-19.) However, many areas that burned in the 1988 fires had not burned since before 1930 and had debris that had been building up for many years. All that debris helped the 1988 fires to spread, leading some people to question the policy.

Some people think that national park land should be artificially maintained. People on this side of the controversy think that people’s needs, wants, and safety should come first. Therefore, all fires should be strictly controlled and put out. In that way, people can continue to use the land for recreation. Other people think that our national parks should go through natural processes. These people support the idea that fires should take their course in order to maintain balance in the forest. Without these fires, wild areas could not regenerate, and wildlife would lose valuable food sources.

Victoria, Australia—February 2009

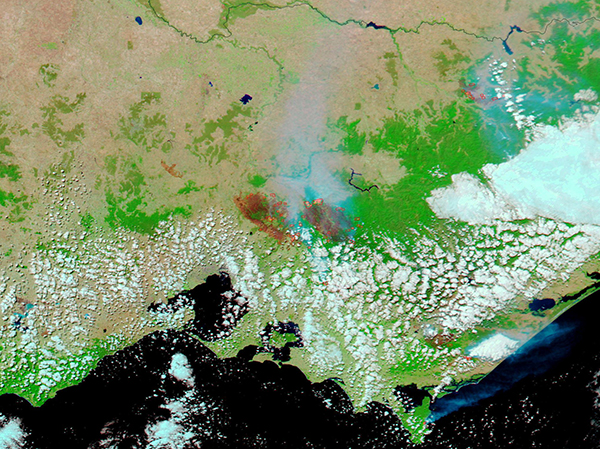

The Black Saturday bushfires began in southern Australia on Saturday, February 7, 2009. (See figures 2-20 and 2-21.) The weather had been very hot and very dry. When the fires started, the temperatures were more than 40°C (110–120°F). Wind speeds were more than 100 kilometers per hour (kph), or 62 miles per hour (mph). There had been little or no rain for several months. As many as 400 separate fires were started. Lightning caused some of the fires. Others were caused by technologies developed by humans, including downed power lines, improper disposal of cigarettes, and sparks from machinery. Some fires were intentionally set by humans (arson). After the fires were put out, they had

- burned more than 1.1 million acres (about 445,000 hectares)

- killed 173 people

- destroyed more than 2,000 houses.

After the fires were out, experts studied them. Their task was to make recommendations that would help protect people from future fires. Their recommendations included improving warning systems, providing education about wildfires, and changing the way buildings are constructed. Hint

MODIS Rapid Response Team

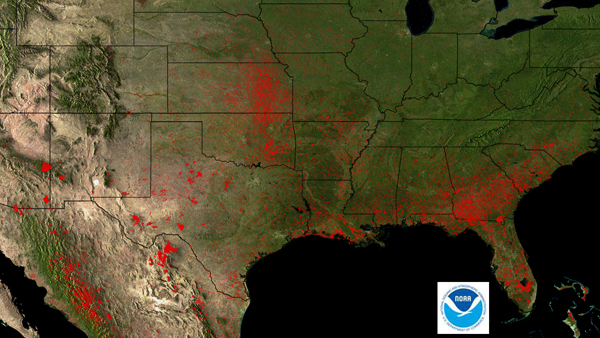

United States—2011

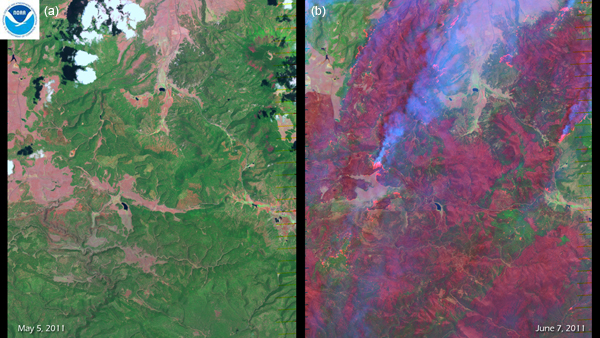

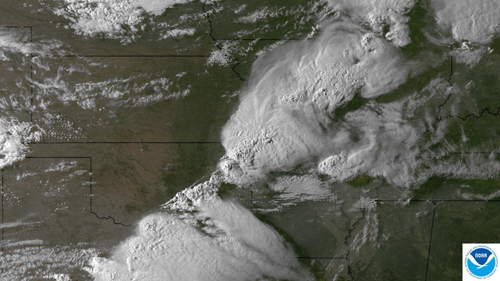

Wildfires caused problems in many parts of the United States in 2011. Between January and the beginning of July, there were more than 36,000 wildfires nationwide. In total, almost 5 million acres (about 200,000 hectares) of land burned. (See figure 2-22.) In many parts of the country, record temperatures and a lack of precipitation increased the chances for fires. Two of the largest fires were in Arizona and New Mexico. The Wallow and the Horseshoe 2 fires in eastern Arizona were caused by humans. Very dry conditions and strong winds made it difficult to put out the fires, and they burned more than 760,000 acres (about 308,000 hectares). The Wallow fire was the largest in Arizona’s history, more than 538,000 acres (about 218,000 hectares). In June 2011, the Las Conchas fire burned more than 94,000 acres (over 38,000 hectares) in northern New Mexico. Strong winds and extreme dryness also made this fire difficult to put out, earning its spot as the largest in New Mexico’s history. More than 1,000 firefighters battled this fire, and the smoke reached as far away as the Great Lakes.

Background Information

Reading 2: Droughts

A drought occurs when a region receives less than normal amounts of rain for several years. A drought is a slow natural disaster. People may die in a severe drought that lasts several years because there is not enough water to grow food. People simply starve. When people are starving, they also are more likely to contract diseases, and they may die from sickness.

Some places on Earth tend to have dry seasons. Usually there is enough rain or snow during the wet season in these places to fill water storage reservoirs. During the dry season, people can use the water stored in the reservoirs to farm the land and to grow food. Then, when there is another wet season, the reservoirs fill up again so there is enough water for the next dry period.

One area may have a drought at the same time that other areas have a wet year. During the summer of 1988, for example, the winds did not carry moist air over Minnesota and Iowa as usual. Instead, they blew the moist air farther over Canada. As a result, Canada was wetter and Minnesota and Iowa were much drier than usual.

Drought affects plants and animals as well as people. During the summer of 1988, people in the United States noticed that some water wildlife was dying. When the ponds received less rainwater than usual, the water level in the ponds went down. As the water decreased, the concentration of a type of bacteria known as clostridia increased. The higher concentrations of clostridia caused many ducks to die of botulism.

Fires are more likely in areas that are having a drought. Plants dry out so much that they can burn more easily. So if a drought happens, fires are more likely. There also is less water to put out the fires. In the summer of 2002, the Rocky Mountains in Colorado were hit hard by forest fires that were worse than normal because of the drought.

Droughts have killed many people throughout history. In China, one drought lasted from 1876 to 1879. It is estimated that up to 13 million people died. People in other parts of China tried to send food, but some people were too weak even to come to the road to get the food. It was also hard for the wagons to get to the center of the drought-stricken area because of poor road conditions.

More recently, droughts in Africa have claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. From 1968 to 1974, a devastating drought affected the Sahel region of Africa. Many of the children who survived suffered from mental retardation. Because they had not had enough to eat when they were very young, their brains could not develop fully. The African country of Ethiopia was hit by a drought that lasted from 1981 into the 1990s. In 2011, the African countries of Kenya, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Somalia (also known as the Horn of Africa) experienced their driest period in 60 years. This drought affected more than10 million people. Population growth, poverty, overuse of land, and war made the effects of the drought more severe.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, Reproduction Number #LCUSF34-004082-E and #LC-USF34-004072-E DLC

Historically, people have not been able to do much to defend themselves from drought. A drought severely affected many parts of the United States in the 1930s. During those years, such states as Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska were part of what was called the Dust Bowl. (See figure 2-24.) The term “dust bowl” refers to the fact that the dried-out soil was picked up by the wind to form large clouds of dust. Sometimes these dust clouds were so thick that they could block the Sun. Drought conditions lasted up to eight years in some areas.

Once the drought of the 1930s was over, people in the United States began to look for ways to protect themselves from drought. People planted trees as windbreaks to slow down soil erosion. This action would help keep the farmland fertile. People also built reservoirs to store water and began to store food for the years when droughts might strike again. Hint

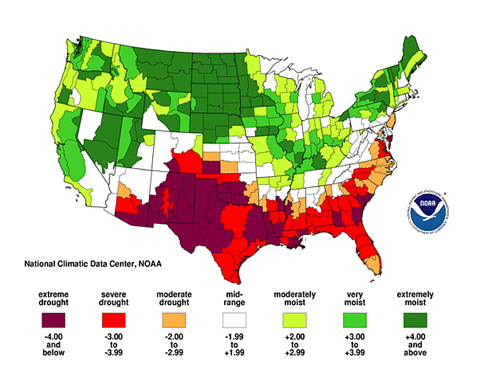

The United States has had droughts after the 1930s Dust Bowl drought. The Great Plains and the southwestern United States experienced a five-year drought in the 1950s. As with the Dust Bowl drought, crop yields dropped as much as 50 percent. Because grasses couldn’t grow, many farmers could not afford to feed their livestock and had to sell them. The next major drought in the United States lasted from 1987 to 1989 and covered about 36 percent of the country. In 2011, parts of the United States again experienced a drought. (See figure 2-25.)

NOAA National Climatic Data Center, State of the Climate: Drought for June 2011, published online July 2011, retrieved from http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/drought/2011/6

Background Information

Reading 3: Floods

Rain and snow are usually good. However, too much of a good thing can sometimes turn into a disaster. The result may be a flood. Floods can occur suddenly or gradually, and they can last for hours or days. As you might have thought already, heavy rain or melting snow is the main cause of flooding. But why would that cause flooding?

Floods happen because of a combination of events. Usually for a flood to occur, three things must happen:

- There must be a heavy rain.

- The soil must be so completely soaked that it cannot hold any more water.

- Streams and rivers must be filled with more water than they can carry. A flood happens when a river overflows its banks.

Floods can happen in a variety of places—everywhere from near the ocean to inland deserts. Sometimes heavy rains occur near the coast. It is easy for the air near a large body of water to gain and then suddenly lose large amounts of water as the clouds move inland. In these coastal areas, floods can occur during or after heavy thunderstorms or during the heavy rains that come with hurricanes. When hurricanes move onto land, a surge of ocean water pushed by winds also can cause flooding.

For places farther inland, floods occur mostly along rivers. Most rivers have channels in which the water usually flows, but they also have flat areas alongside them. The flat area alongside a river is called a floodplain. This is the land where water from a flooded river will go first.

Floods also can occur in areas that are not close to oceans, lakes, or rivers. Sometimes a thunderstorm will occur over a desert area. There are few plants, and the soil cannot absorb all the water. The water rushes down the hillsides and into the valleys below. Places with dry streambeds suddenly fill with rushing water that can throw aside anything in its path. Because these floods occur so suddenly, they are known as flash floods. (See figure 2-26.)

Throughout history, floods have caused millions of deaths. In the United States, flooding is responsible for more deaths than fires, droughts, hurricanes, or tornadoes. Some deaths occur because people do not want to leave their homes or cars.

Two severe floods in the United States happened when thunderstorms occurred near mountain canyons. After one such thunderstorm in 1972 in Rapid City, South Dakota, 232 people died in a flood. In Colorado, the Big Thompson River flood of 1976 killed 139 people. These were tragedies, but they were mild compared with some of the deadliest floods in history. For example, the Yellow River (Huang He or Hwang Ho) of China overflowed its banks in 1887, killing an estimated 800,000 people.

One way that people try to reduce the danger from floods is by building dams on rivers. A dam backs up the water to create a reservoir, which is like a human-made lake. In a heavy storm, the reservoir can hold the extra water that falls over it or falls upstream. Of course, if the storm is downstream the dam can’t help. Expecting a dam to protect people from flooding is not always a good idea.

In addition to helping control floods, dams are also important for generating hydroelectric power. People also use the reservoirs for activities such as swimming, boating, and fishing. For many reasons, it is important that dams are built to be strong and checked regularly for leaks and cracks. A dam that breaks can lead to tragic results. For example, in May 1889, a dam in Pennsylvania failed. This caused the Johnstown flood. In this event, a massive wall of water, mud, trees, and rocks roared down a river valley, killing about 2,100 people. The state of California has recorded 45 dam failures. The worst was the collapse of the Saint Francis Dam in Los Angeles in 1928. (See figure 2-27.) When the dam collapsed, a wall of water over 100 meters (m), or 328 feet (ft) high surged down the canyon, killing at least 450 people. Hint

Do floods ever do any good? For one thing, they can enrich the soil. Some rivers have mild floods every year. Rivers carry organic matter, chemical nutrients, and fine dirt. When a flood recedes, or withdraws, it leaves these materials behind. These substances can help plants grow. During floods, the rivers also wash excess salts out of the soils. Annual flooding makes the soils very fertile. Some of the good farmlands along the Nile River in Africa (See figure 2-28.) and the Mississippi River in the United States were a result of past flooding. When dams are built to stop flooding along a river, as was done to the Nile, the downside can be soil becomes drained of nutrients and no longer produces the same quantity of crops.

Minot, North Dakota—2011

Each year, the melting snow and the spring rains increase the risk for floods in parts of the United States. In 2011, scientists warned about possible floods in areas from Montana to Missouri. (See figure 2-29.) Those warnings turned out to be correct. Floods hit Minot, North Dakota, in June. The floods were caused by above-normal amounts of snow in the northern Rocky Mountains and above-normal rainfall in the spring. More than 11,000 people had to leave their homes. When the Souris River reached its highest level, it broke a high-water record that had stood for 130 years. The river, at its highest, was more than 13 ft (almost 4 m) above flood stage. More than 4,000 homes were damaged—more than 3,200 of those homes were under at least 6 ft (1.8 m) of water.

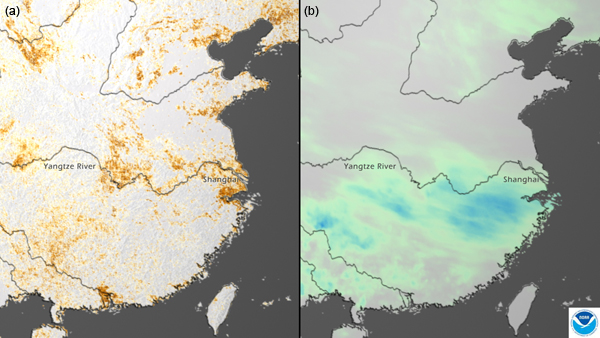

Yangtze River, China—2011

In the spring of 2011, parts of China had their worst drought in 50 years. (See figure 2-30a.) Water shortages affected an estimated 3.5 million people. The drought conditions also made the soil hard. When the rains came (See figure 2-30b.), the dry, hard soil could not absorb the water. Flash flooding became a major problem, and the Yangtze River overflowed its banks. More than 60,000 people had to be evacuated from their homes. Several people were killed or reported missing.

Background Information

Reading 4: Hurricanes

Hurricanes are storms with winds that rotate around a center area of low atmospheric pressure. These storms are called by different names depending on where they occur. They are called hurricanes if they form in the Atlantic or eastern Pacific Oceans. They are called typhoons in the western Pacific Ocean, and cyclones in the Indian Ocean.

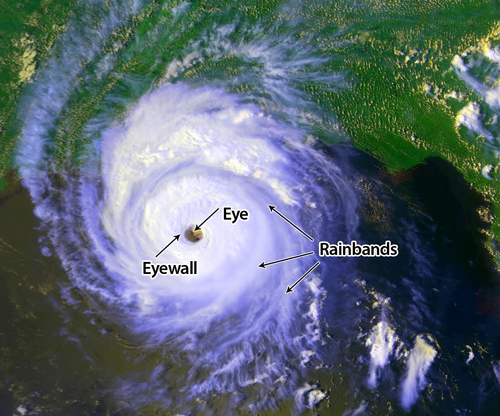

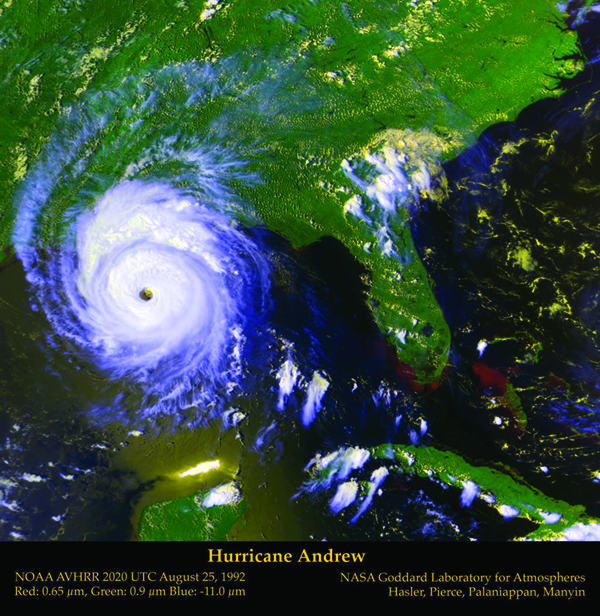

A typical hurricane is about 300 miles (mi) wide, or 480 kilometers (km), but the size can vary greatly. There are three main parts to a hurricane. The eye is the hurricane’s center. (See figure 2-31.) The eye, usually 20–40 mi (32–64 km) wide, is relatively calm. The size of the eye may increase or decrease. The eye wall is the ring of clouds around the eye. The strongest winds are found here. The rainbands are the thick rings of thunderstorms that spiral in from the outer edge of the storm toward the hurricane’s eye.

NASA Goddard Laboratory for Atmospheres. Images produced by F. Hasler, H. Pierce, K. Palaniappan, and M. Manyin. Labels added.

Evaporation and condensation, parts of the water cycle, are important for the formation of hurricanes. Hurricanes initially form over ocean waters that are very warm (at least 80°F, or 27°C) to a depth of at least 150 feet, or 46 meters. Thunderstorms occur in the area before a hurricane can form. The air is warm and moist over these waters. Water evaporates from the ocean, and the water vapor moves into the air. As the warm air rises, it cools. The heat energy that the Sun has stored in the moist atmosphere will be released in the form of condensation, and the winds and rain will increase.

The air pressure is low in the warm, sea-level region where hurricanes form. Pressure differences do not last long, and nearby higher-pressure air moves in quickly. This air movement causes air to circulate in a counterclockwise rotation around the area of low pressure. The eye of the hurricane forms because rapidly sinking air at the center dries and warms the air.

If the winds high in the atmosphere stay relatively light, the storm can continue to strengthen. If weather and ocean conditions continue to be favorable, the system can become a tropical depression (winds less than 38 miles per hour [mph], or 61 kilometers per hour [kph]). At this point, the storm begins to take on the familiar spiral appearance due to the flow of the winds and the rotation of Earth. When the winds reach speeds of 40 mph (64 kph), it is called a tropical storm. The storm becomes a hurricane when the winds reach a minimum of 74 mph (119 kph).

The Coriolis effect also contributes to the spin in the hurricane. As the storm builds in intensity the winds blow around a center portion, which is called the eye of the hurricane. (See figure 2-32.) A hurricane’s eye can be 20–30 miles wide, while the whole hurricane may have a diameter of 400 miles. The eye is calm compared to the storm around it. Inside the eye, if you were to look up, you would see fairly clear skies, and feel little wind. But just beyond the eye you would find the hurricane’s most violent activity. This area is called the ”eyewall.”

The storm drifts slowly to the west because of the winds at high altitudes. As it moves west, it may gradually curve northward. These steering currents are weak, however. The forces within the storm and the energy available in its moisture affect the storm’s path. These circumstances sometimes make predictions difficult.

Hurricanes weaken when their energy supplies get low, for example, when the hurricane moves over cooler water or drier areas. The hurricane’s source of moisture is shut off when the hurricane moves over land. Also, friction from moving over the land reduces the rotation of the winds.

The strong winds can damage ships in the ocean. When the storm makes landfall, the strong winds can cause a great deal of damage. However, the storm surge may be the greatest threat to life and property. A storm surge is a large rush of water that the hurricane winds carry onto the land. A storm surge may be up to 100 mi wide and up to 15 ft deep (160 km wide and 4.6 m deep). Hurricanes can also lead to heavy rains, flooding, and even tornadoes that cause more damage.

The National Weather Service (NWS) uses information from satellites and from radar stations on Earth to track hurricanes. A hurricane watch alerts people living in communities along the coast. When a storm gets closer, the NWS issues a hurricane warning. At this stage, officials may recommend that people evacuate from some areas.

In this animation of Hurricane Katrina (See figure 2-33.), you can watch the 2005 storm from the time it formed in the Atlantic Ocean. You can see the counterclockwise rotation of the storm clouds. The hurricane first made landfall in Florida. It then moved across the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall again near the Louisiana-Mississippi border. It got weaker as it moved over land toward the northeast. Hurricane Katrina was one of the most devastating hurricanes in U.S. history. About 1,200 people lost their lives because of the storm. It is estimated that Hurricane Katrina caused $75 billion in damage in New Orleans, Louisiana, and along the Mississippi coast.

Play Video

Play Video

Another hurricane that is well remembered occurred in Galveston, Texas, in 1900. Galveston is built on a large island off the coast of Texas. People in Galveston knew that hurricanes had hit the island before, but many thought their homes were hurricane-proof. Tragically, these people were wrong. When the 1900 hurricane struck the island, more than 7,000 people were killed. The bridges to the island were destroyed, and people could not escape even when they finally realized that their homes were not safe. Many people drowned. One young woman was able to cling to a floating tree branch, and when the floodwaters finally went down, she found herself 29 km (18 mi) from home. Fortunately, the only injuries she suffered were scrapes and bruises.

Sometimes people forget the lessons of earlier times. When Hurricane Camille struck the coast of Mississippi in 1969, few people were prepared for its strength. Camille was a Category 5 hurricane, the strongest hurricane possible. Homes and buildings along the coast were flooded and smashed. Many people learned that the best way to be safe in a hurricane is to follow the advice from the National Weather Service. When you are advised to evacuate—do so!

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) makes predictions each year about the hurricane season. For 2011, NOAA predicted that there would be an above-normal number of hurricanes in the Atlantic. Scientists base their predictions on information about patterns of hurricane activity in the last few years, ocean temperatures, global wind patterns, and other factors. Of course, scientists cannot be sure where or when hurricanes will form, but , the predictions are still helpful. For example, people may choose not to travel to some areas (especially in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea) during hurricane season. In the areas where hurricanes are more likely, the predictions may help people to better prepare for them. Hint

Background Information

Reading 5: Tornadoes

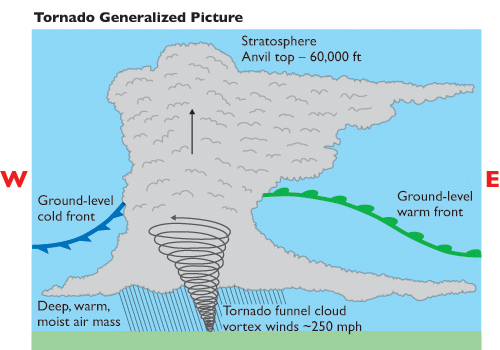

Tornadoes are swirling masses of air with wind speeds from 112 to 480 kilometers per hour (kph) or 70–300 miles per hour (mph). (See figure 2-34.) They can tear a building apart in seconds. Tornadoes strike suddenly and may even accompany hurricanes. Unlike hurricanes, however, tornadoes are more common in certain inland areas.

But what causes tornadoes? To understand what causes tornadoes, think back to what you learned about winds in Chapter 1, "What Causes Weather Patterns?" Remember that air is constantly moving across Earth’s surface. Near the equator, warm air is rising. Near the poles, cool air is sinking. But these air masses—sections of air with similar temperatures and humidity—do not sit still. They move, and sometimes they meet.

Tornadoes are usually rather small. They can, however, reach about 1 mile (mi) or 1.6 kilometers (km) in diameter. It is nearly impossible to predict exactly where a tornado will strike. Buildings in the path of a tornado may be totally destroyed, while nearby structures can be left completely intact.

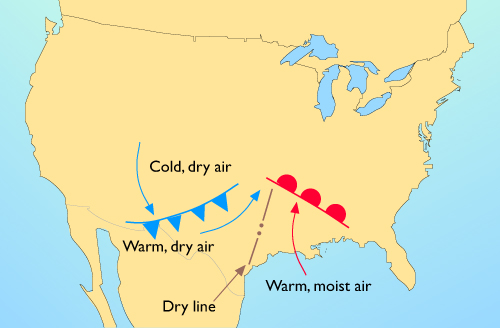

The weather conditions in the spring in the Midwest of the United States are often favorable for tornadoes. Warm, moist air can move in along with south winds from the Gulf of Mexico. During the day, the ground is heated by the Sun, and this causes air movements. (Remember how heat energy from the Sun causes changes in temperature, air pressure, and density?)

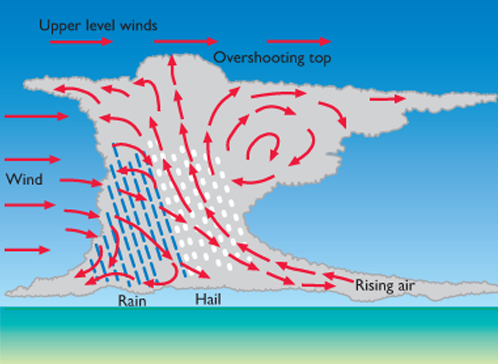

As the warm air rises, it cools, and water vapor condenses. Cumulus clouds form. Cumulus clouds are the puffy clouds that sometimes look like pieces of floating cotton. Condensation releases some heat energy so that this air may end up with a lower density than the air around it. The air continues to lift, and large thunderstorms form. (See figure 2-35.)

The situation can become dangerous when a cold, dry air mass from the west moves rapidly over the warm, moist air mass. This warm, moist air may be much less dense than the cold, dry air. This can cause very sudden, powerful upward movements of air. (See figures 2-36 and 2-37.) The condensation during these thunderstorms releases a large amount of stored energy, and a tornado can develop. A tornado releases forces much greater than ordinary storms do. Wind speeds are very high on the edge of the funnel, and the atmospheric pressure inside the funnel is very low. Buildings are torn apart by the shearing, twisting winds as they are engulfed by the funnel. A tornado is usually short-lived, perhaps lasting only a few minutes—but a lot can happen in those few minutes.

On warm, muggy spring days, you often expect to see clouds develop and rain showers begin. For tornadoes to form, however, other events must be happening high in the atmosphere. The National Weather Service uses weather balloons to gather information. It also uses satellite cameras to spot thunderstorms that are very high. (See figure 2-38.) Radar systems detect the rotation patterns that are typical of tornadoes. The NWS issues a tornado watch when the conditions are right for a tornado to form. During a tornado watch, people should listen for more news and be ready to take action. The NWS issues a tornado warning when someone has actually seen a tornado. When a tornado warning is issued, it is important to seek safe shelter. Because of these warnings, people can be alert and ready to protect themselves. This warning system saves many lives. Hint

Play Video

Play Video

Tri-State Tornado—March 1925

The Tri-State Tornado is believed to be the largest ever recorded in the United States. It struck first in Missouri, then moved to Illinois, and then to Indiana. It lasted for about three-and-a-half hours, far longer than most tornadoes do. On average, it was about three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) wide. Along its path, the tornado killed almost 800 people and injured thousands of others. The Tri-State Tornado was the deadliest tornado in U.S. history. If a tornado like the Tri-State Tornado occurred today, it probably would not be as deadly. The technology we have today would allow people to be warned so they could take precautions. The satellites that scientists now rely on to gather information about weather didn’t exist in 1925. Also, people in 1925 didn’t have the ability to find out information as we do now. Television and the Internet didn’t exist at that time. Many people did not yet even have radios. So even if warnings could have been issued, the technology didn’t exist to quickly inform people about the possible danger.

Joplin, Missouri—May 2011

On May 22, 2011, a thunderstorm tracked from southeast Kansas into southwest Missouri. (See figure 2-39.) This storm produced a tornado that hit Joplin, Missouri. The tornado was about three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) wide and had wind speeds over 200 mph (320 kph). The tornado covered 6 mi (almost 10 km). The Joplin tornado was the deadliest tornado to hit the United States since 1950. More than 150 people were killed, and thousands were injured. This storm generated additional tornadoes and wind damage as it moved across southwest Missouri. These storms also produced flash flooding across far southwest Missouri.

Activity Overview

In this Explain activity, Presenting Events, students will build on their observations of miniature events from the Explore activity. They will work with their teammates to become experts on one of five natural events. They will learn more about

- what causes that type of natural event

- how a natural event becomes a natural disaster

- how the natural event can impact people’s lives

- what people have learned from natural events so that they are better prepared if a similar event happens in the future.

Students also will learn about how technology can help scientists study and monitor natural events.

Before You Teach

Background Information

The following paragraphs provide additional information about natural events to assist you in answering questions from your students.

Tornadoes

Fewer people die from tornadoes today, not only because we know more about these seasonal patterns, but also because we can use satellites and radar to detect weather patterns that indicate the presence of tornadic conditions. Many tornadoes can descend from a single group of clouds. Therefore, in a single day, people may sight many tornadoes that all originate from the same storm front. In Texas in 1967, for example, 115 tornadoes were sighted in one day. For record-keeping purposes, the National Weather Service records the number of days on which tornadoes occur. A “tornado day” is one in which at least one tornado occurs.

Your students may ask you about the difference between a funnel cloud or a waterspout and a tornado. A funnel cloud is a tornado that does not touch the ground. Waterspouts are tornadoes that form over bodies of water.

Hurricanes

Some additional background on pressure may be helpful as students study weather patterns and hurricanes. Pressure is force per area. In a fluid, pressure is the same in all directions. At the bottom of the atmosphere, the pressure is the weight of a vertical column of all the air molecules divided by the cross-sectional area of the column. Because air is compressible, the number of molecules in a given volume is proportional to the pressure. (Remind students about the thought experiment using the pillows in Weather and the Movements of Water and Air in the Atmosphere, the Explain activity in Chapter 1.) As we move up in the atmosphere, the number of overlying molecules per area decreases. Thus, the pressure—and also the density—decreases with altitude. Atmospheric density and pressure decrease roughly 10 percent for each kilometer increase in altitude, and the temperature decreases about 6.5°C for each kilometer (3.5°F every 1,000 feet).

Now consider a 1 cubic centimeter (cm3) volume of air with a certain number of molecules. The air has a certain density, and the molecules are moving with a certain amount of kinetic energy. The kinetic energy per unit volume corresponds to a certain temperature. Now consider moving this volume of air (without losing any energy) to a region where the density is less, and releasing the molecules. They immediately share their kinetic energy with the other molecules. Now the number of molecules in 1 cm3 is fewer and the molecules’ average kinetic energy is lower. The temperature has decreased.

Air that moves quickly from a region of high pressure to a region of low pressure will cool. This might happen in the atmosphere by having a vertical convection current above a heated surface or by having a wind moving up a mountainside (an “upslope” wind) because of a large storm system. This can be demonstrated by releasing the air from a bicycle tire. A thermometer will show that this high-pressure air is lower in temperature than the air in the tire. Conversely, air that moves quickly from a region of low pressure to a region of high pressure will warm up. This might occur if wind were moving down a mountainside. This can be demonstrated by using a hand pump to increase the pressure in the tire. The compressed air in the hose will be warmer than the air surrounding the hose.

An important factor in the energy of a hurricane is the amount of water vapor that evaporates into the atmosphere from a warm ocean surface. Weather satellites are able to observe the size and motion of a hurricane from photographs of clouds. Infrared satellite photographs are able to reveal the amount and motion of water vapor even where clouds are not yet visible. This information is useful for predicting mid-latitude storms as well as tropical storms and hurricanes.

Accurate measurements can also be made of the amount of water vapor in the lower atmosphere, at airports, in backyards, or in buildings. Relative humidity is the amount of water vapor that is present as a percentage of the maximum amount that the atmosphere is able to hold. For example, 100 percent relative humidity occurs with condensation in fog droplets. The relative humidity on a warm, sunny day or inside a heated building is generally much less than 100 percent.

A device that is commonly used to measure relative humidity is the psychrometer. The psychrometer contains a pair of thermometers. The bulb of one of the thermometers is covered with a damp wick, and the bulb of the other thermometer is dry. The dry bulb measures the ordinary temperature. The wet bulb is cooled by the evaporation of moisture from the wick. If the air is dry, the rate of evaporation is high, and the wet-bulb temperature will be several degrees lower than that of the dry bulb. Using these readings, the relative humidity from a calibration chart can be determined. If the air is at 100 percent humidity, it is saturated. No further evaporation can take place, and the dry- and wet-bulb temperatures will be the same.

To obtain an accurate measurement of the surrounding air, the air must move past the thermometers. The sling psychrometer allows you to rotate the thermometers in a circle by hand. For a classroom demonstration, hold the thermometers in a stationary position and ask students to fan the psychrometer for a few minutes with a piece of cardboard. The wet-bulb wick must be moistened occasionally.

Students may ask whether hurricanes occur in places other than the southeastern United States and the Caribbean, and the answer is yes. They occur in the western and southern parts of Asia. In the western Pacific Ocean, they are called typhoons. In southern India, they are called cyclones.

The following are some questions about hurricanes that your students may have:

The center of a hurricane has very low atmospheric pressure. Why don’t the winds rush into this area?

Why aren’t there any hurricanes at the equator?

Where does the hurricane get its energy?

Answer: There is an apparent force, called the Coriolis effect, that is due to Earth’s rotation. This force increases with the speed of the wind and acts toward the right of the wind direction in the Northern Hemisphere. This force balances the force due to the atmospheric pressure difference, and the winds continue to move counterclockwise about the hurricane’s center.

Answer: Earth’s rotation has no effect on horizontal winds at the equator. Winds quickly equalize the atmospheric pressure in this region.

Answer: From the Sun. Radiant energy is gradually stored as the heat of vaporization of evaporated ocean water. When this begins to condense, the energy is released to make strong winds.

Materials

For each student:

- 1 copy of Master 2-2, Natural Events

- pens or pencils of different colors

Advance Preparation

Make 1 copy of Master 2.2, Natural Events for each student.As You Teach

Outcomes and Indicators of Success

By the end of this activity, students will

-

understand the weather-related causes and the effects of fires, droughts, floods, hurricanes, and tornadoes.

They will demonstrate their understanding by

- reading about one type of natural event

- presenting information about that natural event to their classmates

- providing examples about how that type of event can affect people

- describing how humans have learned from natural events to better prepare for similar events occurring in the future.

-

become aware that technology is helping scientists learn about and predict natural events.

They will demonstrate their awareness by describing examples of technologies that have been used to study natural events.

Strategies

Getting Started

Have students look at the chapter organizer and determine what they have learned so far in the chapter. In the Explore activity, they wrote some ideas about how the miniature events they saw at the five stations compared with real-life events. Introduce this activity by informing them that they will examine these natural events in more detail. After their teams learn more about one type of event, they will share what they know with the rest of the class.

Process and Procedure

-

Students should begin the Explain activity by starting a new entry in their technology notebooks.

-

In this activity, students will be reading about one type of natural event (fire, drought, flood, hurricane, or tornado). Assign one natural event to each team, or allow teams to choose. Before beginning the reading, teams should review the observations they made about the miniature event in the Explore activity that matches the natural event they will be reading about. They should discuss the questions in Step 2 with their teammates and write their answers in their technology notebooks.

Note that in the hint, students are told to refer to the student version of How to Develop a Personal Glossary.

The teacher version of

How to Develop a Personal Glossary

can be found at this link.

-

Step 3 asks students to read over a list of questions that they will answer based on information in their assigned reading. These questions should help focus students’ reading and provide guidance.

-

As the teams read about their natural event, if appropriate suggest that students read softly, but aloud, and take turns. When they are finished reading, they can work together to answer the questions about the event.

-

Form new teams. Each new team should include one student who is an expert in one of the different natural events, for a total of five students per team. Give each student a copy of Master 2-2, Natural Events and explain how each member of the new team will teach the other team members about his or her event. In that way, students will learn about each type of natural event, even if they did not complete each reading themselves.

-

Allow time for the new teams to share their knowledge about the different natural events and to complete the handout. Students do not need to write everything about each natural event. For example, they can list one or two examples of how a particular type of natural event might affect people, or one or two examples of changes people have made to better prepare for serious natural events.

You may want to reinforce the idea that each student in the team has a responsibility to teach the other team members. Each team member also has the responsibility to listen carefully and ask questions if he or she needs more information.

-

Lead a brief class discussion and go over the completed Natural Events handout. As part of the discussion, you may want to remind students that all the natural events share the following:

- Science helps us explain why each occurs.

- Some can be very large and cause much destruction. They can range in size or severity.

- People have learned from past events to better prepare for future events.

- Technology can help scientists learn about natural events.